Miranda Rights

@2021-12-23 16:11:32

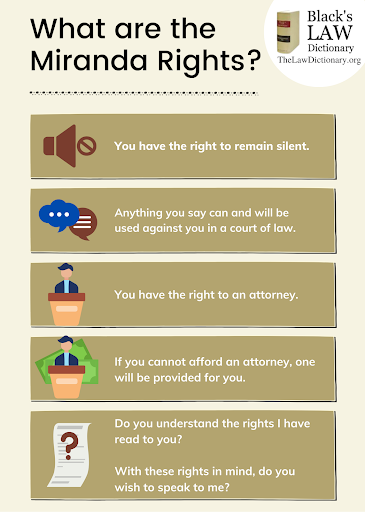

What are the Miranda Rights?

The Miranda warning is a constitutional requirement in the United States given by police to detainees advising them of their right to remain silent, or their right to refuse to answer questions or provide information to law enforcement. This preserves the admissibility of the detainee’s statements made during interrogation in later criminal proceedings.

In other words, if a criminal suspect is asked a question, and they answer the question, that answer can be used against them in a court of law.

Every jurisdiction in the United States has its own regulation regarding what must be said to an arrested individual. Typically, the warning states the following:

- You have the right to remain silent and refuse to answer questions.

- Anything you say may be used against you in a court of law.

- You have the right to consult an attorney before speaking to the police and to have an attorney present during questioning now or in the future.

- If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed for you before any questioning if you wish.

- If you decide to answer questions now without an attorney present, you will still have the right to stop answering at any time until you talk to an attorney.

- Knowing and understanding your rights as I have explained them to you, are you willing to answer my questions without an attorney present?

The Miranda rights don’t need to be read in any order, and don’t need to precisely match the language of the Miranda case as long as they’re conveyed. The rights can be given orally or in writing.

Law enforcement officers are required to administer these rights to protect every detained individual from a violation of their Fifth Amendment rights against unreasonable self-incrimination.

Why are they called “Miranda” rights?

In 1966, there was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case called Miranda v. Arizona (384 U.S. 436) where the Court ruled that the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution restricts prosecutors from using an individual’s statements made during interrogation while in custody unless the individual was informed of the right to consult with an attorney before and during questioning, and also of the right against self-incrimination before questioning. The defendant must not only understand these rights, but also voluntarily waive them.

The case was brought to trial by an incident. On March 13, 1963, the Phoenix Police Department arrested Ernesto Mirando based on indirect evidence. This evidence linked him to a crime occuring 10 days prior where an eighteen-year-old woman was kidnapped and later raped. After two hours of interrogation, Miranda then signed a confession of crimes, including his typed statement, “I do hereby swear that I make this statement voluntarily and of my own free will, with no threats, coercion, or promises of immunity, and with full knowledge of my legal rights, understanding any statement I make may be used against me.”

However, at the time of the signing, Miranda wasn’t told of his right to counsel acquisition. Before the typed form was presented to Miranda, he wasn’t advised of his right to remain silent. And even more, he wasn’t informed that his confession could be used against him in a court of law.

At trial, prosecutors presented Miranda’s written confession as admissible evidence. His court-appointed attorney, Alvin Moore, objected to this because Miranda wasn’t made aware of his right to acquire counsel. Moore argued the confession wasn’t a voluntary one and must be excluded. Unfortunately for Miranda, the objection was overruled based on the confession and on other evidence.

Miranda was convicted of rape and kidnapping and sentenced to 20-30 years of imprisonment for each charge with concurrent sentences.

Miranda’s lawyer, Moore, filed Miranda’s appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court arguing that Miranda’s confession wasn’t totally voluntary and should be deemed inadmissible.

Moore, Miranda’s lawyer, filed Miranda’s appeal to the Arizona Supreme Court, asserting that Miranda’s confession wasn’t completely voluntary and shouldn’t have been admitted into the proceedings. The Arizona Supreme Court reaffirmed the trial court’s original decision to admit the confession in State v. Miranda (401 P.2d 721 (Ariz. 1965)). The Court emphasized Miranda’s lack of requesting an attorney.

Miranda appealed to the United States Supreme Court with attorney John Paul Frank representing him. Gary K. Nelson, attorney, represented the state of Arizona. On June 13, 1966, the Court issued a 5-4 decision in Miranda’s favor. This overturned the conviction and remanded Miranda’s case back to Arizona for a retrial.

Miranda was retried in 1967 after his original case was thrown out. In this case, the prosecution introduced additional evidence, a witness named Twila Hoffman, Miranda’s former roommate. Hoffman testified that Miranda told her he committed the crimes. The Court sentenced Miranda to 20 to 30 years, but Miranda was paroled in 1972.

By: The Blacks Law Dictionary

Comments